Chinese paintings feature some of the world's longest held artistic disciplines and traditions. These paintings with an array of distinctive oriental styles record China's long history and reflect its beautiful landscapes. The following are the 10 most famous paintings of China, in no particular order.

10. One Hundred Horses

"One Hundred Horses" was drawn by Lang Shining in Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Lang was a missionary from Italy with birth name Giuseppe Castiglione. Working as a court painter in China for over 50 years, his talent in painting was regarded highly by Chinese emperors Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong. He helped to create a hybrid style that combined the Western realism with traditional Chinese composition and brushwork.

Lang was skilled at painting horses, and "One Hundred Horses" is one of his representative works. This paper painting, 813 cm long and 102 cm wide, captures 100 horses in various postures. They are kneeling, standing, eating and running on the grassland – staying alone and among groups. The artwork is now preserved in the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

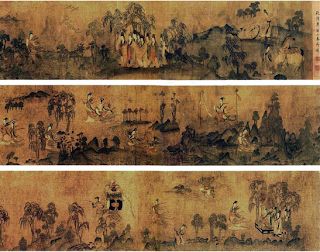

9. Spring Morning in the Han Palace

"Spring Morning in the Han Palace" was drawn by Qiu Ying, who specialized in the gongbi brush technique. He was regarded as one of the Four Great Masters of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Qiu's use of the brush was meticulous and refined, and his depictions of landscapes and figures were orderly and well-proportioned. In addition to his paintings being elegant and refined, they are also quite decorative.

This particular painting is 574.1 cm long and 30.6 cm wide. This hand scroll work is a representation of various daily activities in the palace in the early spring, such as enjoying the zither, watering and arranging flowers, and playing chess. There are 115 characters in the painting, most of them concubines. There are also imperial children, eunuchs and painters. The painting is rendered with crisp brushwork and vivid colors. Trees and rocks decorate and punctuate the garden scenery of the lavish palace architecture.

8.

Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains

"Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains" is the magnum opus and one of the few surviving works by the painter Huang Gongwang in the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). Many consider him a member of the "four great masters of the Yuan." He spent his last years in the Fuchun Mountains near Hangzhou and completed this painting in 1350.

The painting was drawn in black ink on paper. It vividly portrays the beautiful landscape on the banks of Fuchun River, rendering the mountains, trees, clouds and villages and capturing the essence of the natural scenes in Southern China. It is regarded as the best landscape ink painting in China's art history.

Unfortunately, the masterpiece was damaged by fire and split into two pieces in 1650. Today, the first piece, 51.4 cm long and 31.8 cm wide, is kept in the Zhejiang Provincial Museum in Hangzhou, while the second piece, 636.9 cm long and 33 cm wide, is kept in the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

7.

A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains

"A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains" by Wang Ximeng, Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), is a landscape painting masterpiece of ancient China. It is now part of the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing.

Wang was one of the most renowned palace painters of the time. He became a student of the Imperial Painting Academy, and was taught personally by Emperor Huizong of Song. He finished this painting when he was only 18. Unfortunately, as a genius painter, he died very young in his 20s.

The hand scroll is 1,191.5 cm long and 51.5 cm wide. Heavy ink strokes of black and other colors vividly depict mountains, lakes, villages, houses, bridges, ships pavilions and people. It is one of the largest paintings in Chinese history and has been described as one of the greatest works.

6. Han Xizai Gives A Night Banquet

"Han Xizai Gives A Night Banquet" is a scroll drawn by Gu Hongzhong, a painter in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907-960). It is now housed in the Palace Museum in Beijing.

The main character Han Xizai in the painting was a high official in Southern Tang, but later attracted suspicion from the Emperor Li Yu. To protect himself, Han pretended to withdraw from politics and become addicted to a befuddled life full of entertainment. Li sent Gu from the Imperial Academy to record Han's private life, leading Gu to produce this famous artwork.

This painting, depicting scenes of Han's banquet, narrates through five distinct sections: Han Xizai listens to the pipa (a Chinese instrument) with his guests; Han beats a drum for the dancers; Han takes a rest during the break; Han listens to the wind music; and the guests talk with the singers. There are more than 40 characters in the paintings, all of the lifelike figures with different expressions and postures. The painting was Gu's most well-known work, as well as one of the most outstanding artwork from the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

5.

Five Oxen

"Five Oxen" is a painting by Han Huang, a prime minister in the Tang Dynasty (618–907). The painting was lost during the occupation of Beijing by the Eight-Nation Alliance in 1900 and later recovered from a collector in Hong Kong during the early 1950s. Now it is stored in the Palace Museum in Beijing.

The painting is 139.8 cm long and 20.8 cm wide. The five oxen in varied postures and colors in the painting are drawn with thick, heavy and earthy brushstrokes. They are endowed with subtle human characteristics, delivering the spirit of the willingness to bear the burden of hard labor without complaints.

Most of the paintings recovered from ancient China are of flowers, birds and human figures. This painting is the only one with oxen as its subject that are represented so vividly, making the painting one of the best animal paintings in China's art history.

4. Noble Ladies in Tang Dynasty

"Noble Ladies in Tang Dynasty" are a serial of paintings drawn by Zhang Xuan and Zhou Fang, two of the most influential figure painters during the Tang dynasty (618–907), when the paintings of noble ladies became very popular.

The paintings depict the leisurely, lonely and peaceful life of the ladies at court, who are shown to be beautiful, dignified and graceful. Zhang Xuan was famous for integrating lifelikeness and casting a mood when painting life scenes of noble families. Zhou Fang was known for drawing the full-figure court ladies with soft and bright colors.

The paintings are spread around in the collections of museums nationwide.

3. Emperor Taizong Receiving the Tibetan Envoy

"Emperor Taizong Receiving the Tibetan Envoy" painter Yan Liben was one of the most revered Chinese figure painters in the early years of the Tang dynasty (618–907). The painting is a work of both historical and artistic value, collected by the Palace Museum in Beijing.

The painting is 129.6 cm long and 38.5 cm wide, drawn on the tough silk, depicting the friendly encounter between the Tang dynasty and Tubo in 641.

In the painting, the emperor sits on a sedan surrounded by maids holding fans and canopy. He looks composed and peaceful. On the left, one person in red is the official in the royal court. The envoy stands aside formally and holds the emperor in awe. The last person is an interpreter.

2. Nymph of the Luo River

"Nymph of the Luo River" by Gu Kaizhi of Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420) illustrates a romantic poem by Cao Zhi from the state of Wei during the Three Kingdoms period. The copy collected by the Palace Museum in Beijing is a facsimile of the original made during the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

The narrative silk scroll depicts the meeting and the eventual separation of Cao Zhi and the Nymph of the Luo River; the art captures the tension through the composition of the figures, stones, trees and mountains. The painting is one of the most important Chinese artworks, representing the beginning of the development of Chinese landscape paintings.

1.

Riverside Scene at Qingming Festival

"Riverside Scene at Qingming Festival" is a panoramic painting by Zhang Zeduan, an artist in the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). It is the only existing masterpiece from Zhang, and has been collected by the Palace Museum in Beijing as a national treasure.

The hand scroll painting is 528.7 cm long and 24.8 cm wide. It provides a window to the period's economic activities in urban and rural areas, and captures the daily life of people of all ranks in the capital city of Bianjing (today's Kaifeng, Henan Province) during Qingming Festival in the Northern Song Dynasty. It is an important historical reference material for the study of the city then as well as the life its residents rich and poor.

The painting is composed of three parts: spring in the rural area, busy Bianhe River ports, and prosperous city streets. The painting is also known for its geometrically accurate images of variety natural elements and architectures, boats and bridges, market place and stores, people and scenery. Over 550 people in different clothes, expressions and postures are shown in the painting. It is often considered to be the most renowned work among all the Chinese paintings, and it has been called "China's Mona Lisa."